In my prior post, IBM Watson: The Legal Market at World of Watson Conference, I reported on my IBM’s World of Watson conference. Here, I offer thoughts about Watson and the business model to support it in the legal market.

Legal Market Increasingly Receptive to IBM Watson and AI

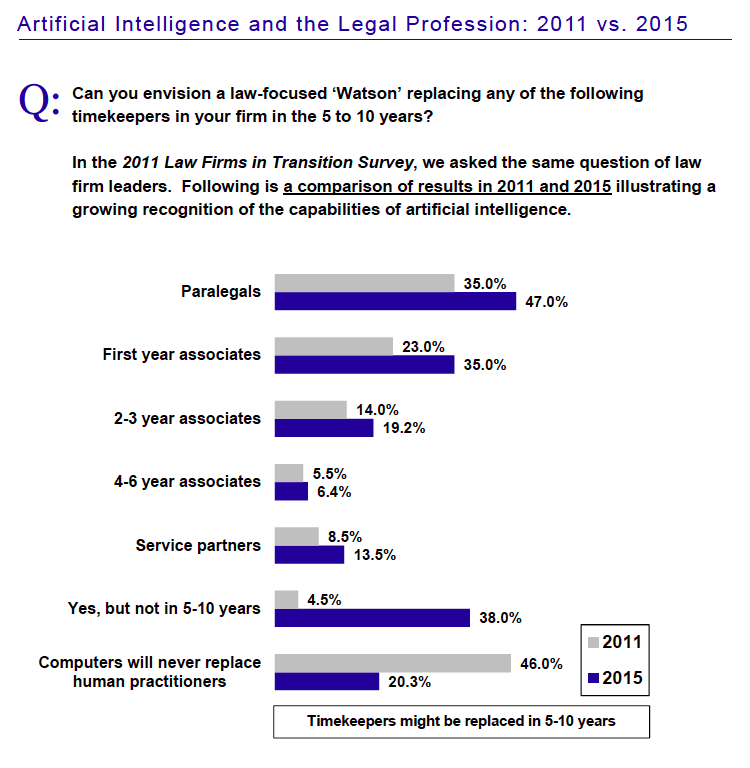

The May 2015 Altman Weil law firm survey Law Firms in Transition 2015 shows that law firm managers’ views on Watson’s potential are quite positive:

What is the Legal Watson Business Model?

Many in the legal market see Legal Watson potential but the business model to support it remains unclear. Last August in Meet Your New Lawyer, IBM Watson I asked three questions:

- What information – and how much – does Watson need to ingest and, to the extent necessary, who will tune or train it?

- If Watson ingests enough and is tuned, will it exercise good legal judgement?

- If its judgement is good, what business model supports building the system?

From what I have learned, the answer to the business model question probably depends on the choice of Watson “reasoning modes” (my words). Watson offers multiple modes. I suspect that the selection significantly affects the business model.

Sexiest Legal Watson Applications Likely Require Many Q&A Pairs

Legal Publishers May be the Winners. I believe that the “sexiest” Legal Watson applications – those that answer questions – will work better for legal publishers or others selling content to big audiences. If I am right – and that may be a big if – that would limit law firm use.

Answering Questions Requires Question & Answer Pairs – and Training. I recently learned (via others who share my interest in Watson), that to answer questions, Watson needs a large number of question and answer pairs. Given many pairs, Watson finds the answers most related to a question. Note that Q&A pairs alone do not suffice. Developers must also train Watson by asking a lot of questions, reviewing answers, and tuning the system. This strikes me as time-intensive tasks for well-trained professionals – which translates to expensive.

Law Firms Lack Sufficient Q&A Content. For Q&A applications, I wonder how anyone can, without pre-existing or enormous new resources, build such a system. Very little off-the-shelf legal material (private or public) exists in that format. Coming closest is the classic law firm research memo, with its “question presented” followed by an answer. But I doubt even large law firms have enough current research memos to feed Watson.

Legal Publishers May Have Enough Q&A Content. Published secondary source material might shoehorn into the Q&A paradigm. West headnotes, for example, state points of law and point to specific sections of decisions (meaning some potential to treat the the headnote as a question and the corresponding text as an answer). Likewise, some legal treatises present in a format with many headings (“questions”) and associated short blocks of text that are answers.

Q&A Approach Likely Requires a Big Market. If Q&A works as a technical matter, it still leaves open the the business model question. Legal publishers might have an incentive to deploy Watson and be able to charge enough across their big customer base to make money. I doubt law firms can do the same. US law firms barely invest in any non-billable substantive work so would have trouble building the system. And they sell to a tiny audience, not a large audience, which seems key to profitability.

Examples of Existing Legal Watson Applications

Let’s review existing legal Watson applications to see what we can learn…

- Start-up company ROSS, which emerged from an IBM-hosted Watson competition at the University of Toronto, does use the Q&A mode. According the Globe & Mail (11 Dec 2015), ROSS allows users to ask about Ontario law and the system provides the best answer. This is a new company so we know little about its business model.

- LegalOnRamp uses of Watson to process and understand high volumes of contracts, which is described in IBM Watson: It’s (Almost) Elementary (Metropolitan Corporate Counsel, 12 May 2015).” That suggest Watson can also extract key terms from large volumes of contracts. I believe Watson supports LOR’s existing business model.

- Intelligent Choice (Partner Magazine, April 2015) discusses Manchester (UK)-based DWF LLP, which is working with Watson’s labs in Dublin. DWF “is developing an Al tool that automatically allocates new work sent in by its volume-based clients… it draws on data contained in the firm’s case management files which… helps the tool predict a new matter’s likely legal complexity.” We have no information about the economics.

So we really cannot learn very much about the Legal Watson business model from known applications. But of the three, only one appears to use the Q&A mode.

Concluding Thought: Comparing Watson to Alternatives

Other ways exist to automate answering legal questions. How do we assess the cost/benefit of Watson with alternative approaches? For example, expert systems from Neota Logic answer questions via an interactive Q&A session. Expert systems and cognitive computing are completely different computing approaches. From the business and practical perspective, the important question is the cost to build each and the size of the market it can serve.

More generally, if we aim to improve the efficiency of the legal market, there is no lack of technology to choose from. Whether Watson is the best place to bet remains an open question. I remain enthusiastic about Watson but still have many questions.

Archives

Blog Categories

- Alternative Legal Provider (44)

- Artificial Intelligence (AI) (57)

- Bar Regulation (13)

- Best Practices (39)

- Big Data and Data Science (14)

- Blockchain (10)

- Bloomberg Biz of Law Summit – Live (6)

- Business Intelligence (21)

- Contract Management (21)

- Cool Legal Conferences (13)

- COVID-19 (11)

- Design (5)

- Do Less Law (40)

- eDiscovery and Litigation Support (165)

- Experience Management (12)

- Extranets (11)

- General (194)

- Innovation and Change Management (188)

- Interesting Technology (105)

- Knowledge Management (229)

- Law Department Management (20)

- Law Departments / Client Service (120)

- Law Factory v. Bet the Farm (30)

- Law Firm Service Delivery (128)

- Law Firm Staffing (27)

- Law Libraries (6)

- Legal market survey featured (6)

- Legal Process Improvement (27)

- Legal Project Management (26)

- Legal Secretaries – Their Future (17)

- Legal Tech Start-Ups (18)

- Litigation Finance (5)

- Low Cost Law Firm Centers (22)

- Management and Technology (179)

- Notices re this Blog (10)

- Online Legal Services (64)

- Outsourcing (141)

- Personal Productivity (40)

- Roundup (58)

- Structure of Legal Business (2)

- Supplier News (13)

- Visual Intelligence (14)